Building Acceptance Tests with Playwright using a 4 layer model

or: How I learned to accept tests and fixture the whats

Acceptance tests, the high level tests focused on what a system does are a key tool in faster and higher quality releases. Releasing frequently is a sign of a high performing team according to DORA metrics, but frequency alone isn’t enough - you need confidence in what you’re deploying. Nobody wants to “deploy and pray” multiple times a day. So you need a way of testing the system before it is deployed. While there are multiple layers of testing available to us, acceptance tests play a crucial role by verifying the system behaves correctly from the user’s perspective.

This is especially important because your system likely has multiple ways for users to interact with it - from different UIs, to API tools, to chat bots. You expect your system to work consistently across all these interfaces when making a change.

So having a way of writing down what the system does, independent of any specific interface, is incredibly liberating when creating acceptance tests.

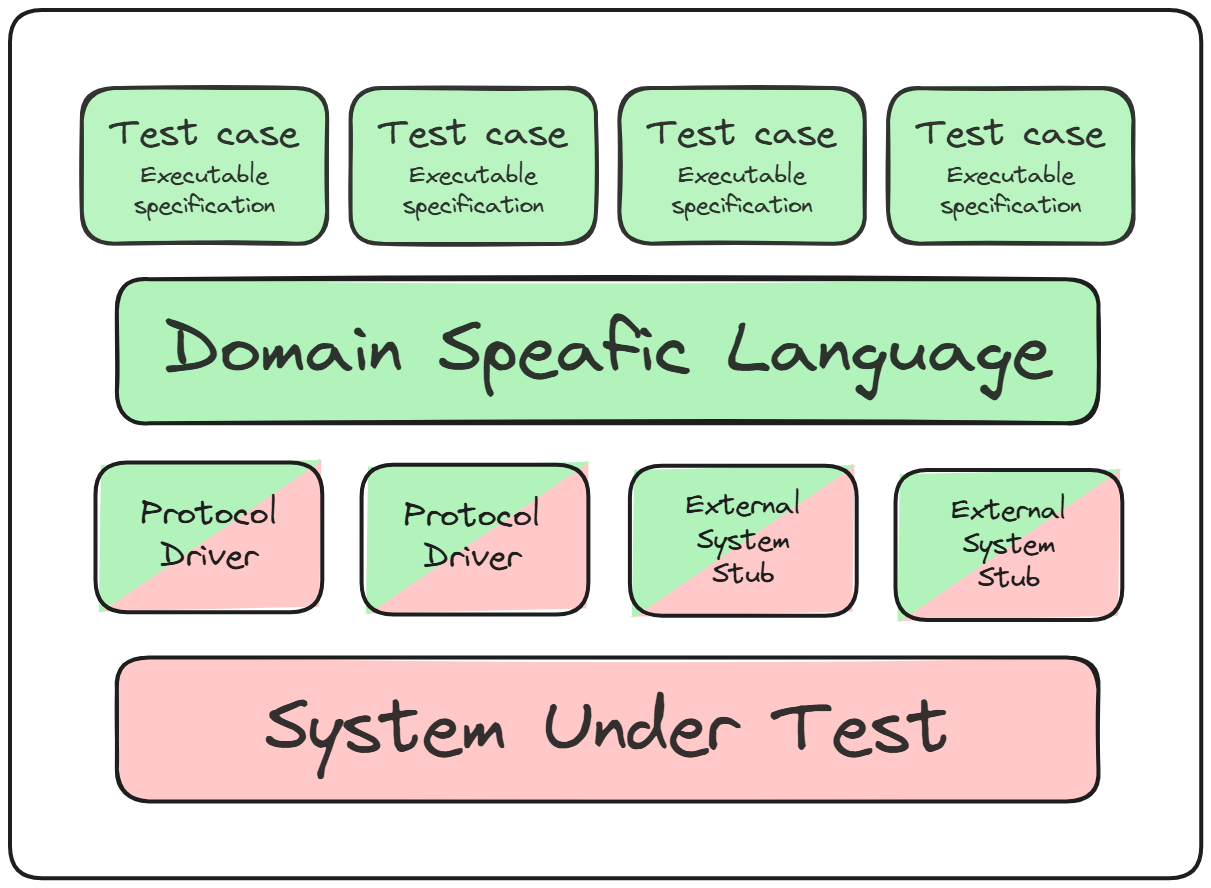

The 4-layer test model, championed by Dave Farley in Continuous Delivery1 2 3, provides a clear structure for acceptance testing. Playwright and its test runner give us the perfect foundation for implementing this model.

Four layer separation of concerns model

For these acceptance tests the 4 layer model gives us a way of writing tests independent of the system under test and how the testing tool interacts with the system.

Let’s look at each layer:

Domain Specific Language

The core interface describing what our system does, implemented as TypeScript interfaces.

interface BlogPost {

title: string;

content: string;

publishDate: Date;

description?: string;

}

type PostSelector =

| { type: 'title'; title: string }

| { type: 'position'; position: number }

| { type: 'date'; date: Date };

export interface AdamSandersonBlogDSL {

// Core behaviors

accessPost: (selector: PostSelector) => Promise<void>;

listPosts: () => Promise<void>;

// Expectations

expectPostsToExist: () => Promise<void>;

expectPostExists: (selector: PostSelector) => Promise<void>;

expectPostContent: (selector: PostSelector, expectedContent: string) => Promise<void>;

expectPostsInOrder: (posts: BlogPost[]) => Promise<void>;

expectAuthorToBe: (name: string) => Promise<void>;

}

This is the DSL for this blog. At it’s core you can do two things right now, get a list of posts and get one of the posts. We can see there are different ways of selecting a post and information we can get from a post. There is nothing specific about the implementation here, just a high level look at what the system should do.

Protocol Drivers

The protocol driver is an implementation of our DSL, in this case using Playwright to interact with the website. Each driver translates the high-level DSL operations into concrete actions for a specific interface.

import { type AdamSandersonBlog } from './adamsanderson.dsl';

import { expect, type Page } from '@playwright/test';

export class AdamSandersonCoUkWeb implements AdamSandersonBlog {

private baseURL: string;

protected page: Page;

constructor(page: Page, baseURL: string) {

this.page = page;

this.baseURL = baseURL;

}

accessPost: AdamSandersonBlog['accessPost'] = async (selector) => {

if (selector.type === 'title') {

await this.page.getByText(selector.title).click();

return;

}

throw new Error('Selector not implemented');

};

listPosts: AdamSandersonBlog['listPosts'] = async () => {

await this.page.goto(this.baseURL);

};

expectPostsToExist: AdamSandersonBlog['expectPostsToExist'] = async () => {

await expect(

this.page.getByRole('link', { name: 'From Bootstrap - How to make a point with CSS' })

).toBeVisible();

};

expectPostExists: AdamSandersonBlog['expectPostExists'] = async (selector) => {

if (selector.type === 'title') {

await expect(this.page.getByRole('heading', { name: selector.title })).toBeVisible();

}

};

expectPostContent: AdamSandersonBlog['expectPostContent'] = async (selector) => {

throw new Error('Not implemented' + selector);

};

expectPostsInOrder: AdamSandersonBlog['expectPostsInOrder'] = async (posts) => {

throw new Error('Not implemented' + posts);

};

expectAuthorToBe: AdamSandersonBlog['expectAuthorToBe'] = async (name) => {

await expect(this.page.getByText('Adam Sanderson')).toBeVisible();

};

}

This protocol driver utilizes Playwright’s page object to navigate the site and verify content. Notice how it encapsulates all the implementation details while maintaining the clean interface defined by our DSL. We have similar drivers for keyboard navigation and RSS, allowing us to test multiple interfaces with the same test cases.

Test Framework

With our DSL and protocol drivers in place, our acceptance tests become simple and focused on behavior. Then using Playwright tests with fixtures to inject the appropriate protocol driver. This layer connects our DSL implementation to the test runner, allowing each test to work with any of our protocol drivers.

type FixtureTestArgs = {

adamSandersonCoUk: AdamSandersonBlog;

logger: typeof logger;

performance: PagePerformance;

};

function getAdamSandersonBlog(projectName: string, page: Page, baseURL: string) {

if (projectName === 'RSS') {

return new AdamSandersonBlogRSS(baseURL);

}

if (projectName === 'chromium - keyboard') {

return new AdamSandersonCoUkWebKeyboard(page, baseURL);

}

return new AdamSandersonCoUkWeb(page, baseURL);

}

export const test = base.extend<FixtureTestArgs>({

adamSandersonCoUk: async ({ page, baseURL }, use) => {

const adamSandersonCoUk = getAdamSandersonBlog(

test.info().project.name,

page,

baseURL || 'http://localhost:5173'

);

await use(adamSandersonCoUk);

},

logger: async ({}, use) => {

await use(logger);

},

performance: async ({ page }, use) => {

await use(new PagePerformance(page));

}

});

The power of this approach comes from how Playwright fixtures work. The getAdamSandersonBlog function selects the appropriate protocol driver based on the current project configuration, allowing us to run identical tests across different interfaces without changing any test code.

Then we have the acceptance tests, a selection of simple tests of behaviour. Run against each configured project, so multiple browsers, input methods and interfaces.

test('Expect to get a list of posts', async ({ adamSandersonCoUk }) => {

await adamSandersonCoUk.listPosts();

await adamSandersonCoUk.expectPostsToExist();

});

test('Expect to get content for a selected post', async ({ adamSandersonCoUk }) => {

await adamSandersonCoUk.listPosts();

await adamSandersonCoUk.expectPostsToExist();

const selectPost = {

type: 'title',

title: 'From Bootstrap - How to make a point with CSS'

} as const;

await adamSandersonCoUk.accessPost(selectPost);

await adamSandersonCoUk.expectPostExists(selectPost);

});

test('Expect that I am identified as the author', async ({ adamSandersonCoUk }) => {

await adamSandersonCoUk.listPosts();

await adamSandersonCoUk.expectPostsToExist();

await adamSandersonCoUk.expectAuthorToBe('Adam Sanderson');

});

System Under Test

This blog is the system under test.

Conclusion

The four layer model unlocks an ability to create long term stable reliable tests, that can be the basis of a system that allows for a high frequency of reliable deployments. Helping teams become elite performers. The separation of what the system does from how it does it allows us to change implementations without touching the tests. Allowing for structural changes to the code with confidence, and making it clear when there are behavioural changes to the code.

We can see these benefits in practice with our example. By implementing protocol drivers for both web UI and RSS interfaces, we can run the same acceptance tests against two completely different ways of interacting with the site. The tests remain focused on the behaviour we care about, while the drivers handle the specifics of each interface.

This approach scales beyond just web and RSS - new interfaces can be added by implementing a new protocol driver such as a keyboard driven version of the UI for a11y testing, a legacy and modern versions for a migration between platforms, prompts could be sent to an AI API and the responses evaluated with evals in the expectations. All while our tests remain focused on the core behaviour of our system.